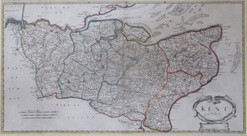

Camden's Britannia, one of the best known 17th and 18th century atlases of the British isles, was the perfect vehicle for the talented young mapmaker Robert Morden. Working in the map-making hotbeds of the bustling London areas of New Cheapside and later, Cornhill, Morden plied his trade at The Atlas between the years 1675 and roughly 1703, producing quality county maps covering England and Wales. Published by William Camden, Britannia ran for four editions (1695, 1722, 1753 and 1772) using Morden's fine maps.

Having worked on them prior to his commission by Camden, Morden also released a considerably smaller set of his county maps, more akin to Thomas Kichin's set of small copper county maps than to those Morden used to illustrate Britannia. These maps are considerably rarer and referred to as 'Mini' or 'Miniature' Mordens. Scarcity aside, they are still not considered as collectable as a pristine collection of his Britannia maps.

In contrast to the previous century's style of maps, Morden simplified his presentation: veering away from the highly decorative and highly embossed maps of Speed, Blaeu and the like and focussing on clarity of detail. Camden had previously used William Kip's reduced versions of Saxton's 1574 county maps for Britannia, but Morden's cleverly simplified plates are now synonymous with the great publication.

Even John Cary's later re-workings of his own and Morden's Camden plates, used for Britannia next edition in 1789, appear almost indelicate and overly-complicated and overall a slightly coarser collection. Some might see this simply as cartographic evolution at work, and of course this has been the case since Ptolemy's trapezoid projection ruffled feathers two centuries earlier and Mercator stretched the world to fit on to a flat page. Progression aside, Morden's Britannia maps were easy on the eye and yet detailed to boot.

Most of these were published uncoloured and remain so, or have been coloured at a later date, often in Victorian times. Some, however, and it is a very small proportion, of the first (1695) edition, were published with quality outline hand colouring denoting county boundaries and the various Hundreds within the counties. Unfortunately, due to the sometime acidic nature of the paint used, many of these beautiful coloured maps suffered from paper weakening leading to eventual paper loss or tearing, or left in dire need of restoration. Thankfully, this only happened to some, and there are still a small number of these highly sought, 1695 edition maps with original hand colour.

It has been noted that the one element of the older, more decorative style of mapping, can be found when Morden need to depict mountainous areas on his maps. Hilly areas, such mas the Lake District (counties of Cumberland & Westmoreland at the time) and some areas of Wales (Monmouthshire in particular), are shown with a wealth of artistically engraved hills, not strictly accurate in dimension, but considered enough to show relative heights within the group of hills and add a certain aesthetic, lost on many later maps.

Having worked on them prior to his commission by Camden, Morden also released a considerably smaller set of his county maps, more akin to Thomas Kichin's set of small copper county maps than to those Morden used to illustrate Britannia. These maps are considerably rarer and referred to as 'Mini' or 'Miniature' Mordens. Scarcity aside, they are still not considered as collectable as a pristine collection of his Britannia maps.

In contrast to the previous century's style of maps, Morden simplified his presentation: veering away from the highly decorative and highly embossed maps of Speed, Blaeu and the like and focussing on clarity of detail. Camden had previously used William Kip's reduced versions of Saxton's 1574 county maps for Britannia, but Morden's cleverly simplified plates are now synonymous with the great publication.

Even John Cary's later re-workings of his own and Morden's Camden plates, used for Britannia next edition in 1789, appear almost indelicate and overly-complicated and overall a slightly coarser collection. Some might see this simply as cartographic evolution at work, and of course this has been the case since Ptolemy's trapezoid projection ruffled feathers two centuries earlier and Mercator stretched the world to fit on to a flat page. Progression aside, Morden's Britannia maps were easy on the eye and yet detailed to boot.

Most of these were published uncoloured and remain so, or have been coloured at a later date, often in Victorian times. Some, however, and it is a very small proportion, of the first (1695) edition, were published with quality outline hand colouring denoting county boundaries and the various Hundreds within the counties. Unfortunately, due to the sometime acidic nature of the paint used, many of these beautiful coloured maps suffered from paper weakening leading to eventual paper loss or tearing, or left in dire need of restoration. Thankfully, this only happened to some, and there are still a small number of these highly sought, 1695 edition maps with original hand colour.

It has been noted that the one element of the older, more decorative style of mapping, can be found when Morden need to depict mountainous areas on his maps. Hilly areas, such mas the Lake District (counties of Cumberland & Westmoreland at the time) and some areas of Wales (Monmouthshire in particular), are shown with a wealth of artistically engraved hills, not strictly accurate in dimension, but considered enough to show relative heights within the group of hills and add a certain aesthetic, lost on many later maps.